“One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever.”

– Ecclesiastes 1:4

Note: We have been consistently concerned about very high valuations in the global investing markets as well as a growing set of participants whose investment patterns are gambling-like. While we remain concerned about those things, in this newsletter we will examine an argument we’re hearing used to explain the increased attention (and value) in crypto assets. We won’t be endorsing cryptocurrencies here[1]. We’re just looking to highlight an argument we have heard favoring the world of crypto assets with our goal to make us all think. A large part of our job is to look at a plethora of low probability events and identify when one of those event’s probability increases enough to pose a risk to our clients’ savings. We see the notion that crypto will supplant the world’s fiat currencies as a low probability. However, if it were to mature, it could have a large impact that we all need to understand.

Let’s start with a story…

Several young people find themselves on an island, away from civilization. They split up functions and chores to survive in this new land. They decide they need a currency—rabbit pelts—to represent the value of the goods and services they trade among themselves. Eventually, a few of them determine it is easier to farm rabbits than to hunt them, creating a more plentiful supply of pelts (as well as rabbit stew, recipe here).

Though farming made pelts easier to come by, the islanders began capping production (or as the elders put it, “regulating”) rabbit farming to sustain equality and to hold up the value of the pelts. Life settled down and became pleasant for most. The island’s occupants began to focus on family creation and fine-tuning their lives. Next came simple forms of financial engineering, such as credit (e.g., Islander A promises to deliver four rabbit pelts to Islander B once Islander A receives a future payment of pelts from Islander C). And on it went, with consumption growth fueled in part by a growing pelt credit market.

A bad winter or a hot summer decreased the rabbits’ litters, straining the trading of services every so often, and, if the weather stayed poor longer than expected, putting the pelt credit system under significant stress. Many of the elders (our young people are aging now) had abundant pelt savings, and many lent their pelts out. During prolonged bad weather, these elders feared borrowers would default; they felt they risked substantial losses. Due to this concern, the elders of the community permitted rabbit farming to be ramped up as a means of keeping people confident they would get through the seasonal extreme. Of course, the elders wanted to maintain a high degree of control over the rabbit farms because they considered them instrumental to the health and wellbeing of society.

The original islanders were happy with the system because most of their savings were in investments backed or priced in rabbit pelts. However, the growing number of young people were becoming disenchanted with the financial system their parents had created. And with the financial system touching so much of life’s activities, the frustration grew to include the political structure of the island. Among this newer generation, there was growing concern that the laws and the economy were skewed to favor a select few and that regulations were not being applied fairly. The young thought the system that worked so well for their parents was leaving them out.

These whispers from the young turned into screams. The social fabric appeared strained as demonstrations were becoming commonplace. Many of the demonstrations showed a deep frustration with the system rather than any particular outcome of the system. The frustrations grew to a point where some young ones devised a solution to, at least, address the financial aspects of their issues.

Some of the young began thinking up a new system, one that worked on their terms rather than their parents’. Although they still used rabbit pelts to trade, they also began holding some of their savings in a digital form. (Yes, our society has developed computers! Please suspend disbelief.) The young wanted an asset that was considered precious. They determined that scarcity was inherently valuable, as was the ability to trade without permission from the elders. To that end, a young one (for fun, let’s call him Satoshi Usagi[2]) developed a mathematical algorithm with a finite output, forcing the amount of the output to be fixed. As a side note, the processing power required to obtain output from the algorithm was substantial, making the task of creating the algorithm’s output increasingly costly as it approached its maximum. This was counter to what they experienced with the elders and rabbit pelts where the incremental pelt became easier to justify.

The young ones were enamored with the idea that this algorithm could produce only so much, that its scarcity could not be modified by the elders, and that the elders were not influencing the activities of the algorithm. Though there was no hard asset underlying the algorithm’s value, the young ones argued that the lack of discipline in farming rabbit pelts had eroded their faith that the pelts would retain value, especially as the elders were farming them at an ever-faster rate.

Back to our reality…

The Federal Reserve is once again believing its own blather, thinking it can solve all problems. Y2K? Easy. Mortgage bubble? You bet. European banking crisis? In our sleep. Pandemic? We’re just warming up. Income inequality? Why not give us something hard? Climate Change? Let us sharpen our pencil.

As the bankers’ bank and the lender of last resort, the Federal Reserve sees itself as infallible. Yet, history would suggest it is not. The current academics on the Federal Reserve Board have done an amazing job studying the Great Depression to prevent today the mistakes of that era. They are open to discussing their fears that deflation could evolve into a deep and prolonged economic hardship. However, the current board should spend more time reviewing the 1960s and ’70s.

It is becoming obvious that today’s Fed members must not have read Paul Volcker’s book Keeping At It, nor absorbed his core belief in a stable value for the U.S. dollar. For those that may not remember, Volcker was the chairman of the Federal Reserve that broke the back of inflation in the late 1970s and early ’80s. He reflects in his book on the high inflation then taking hold in the U.S., and his belief that we needed to break it, no matter how painful. “[The need to focus on price stability] enforced upon the Federal Reserve an internal discipline that had been lacking: we could not back away from our newfound emphasis on restraining the growth in the money supply without risking a damaging loss of credibility that, once lost, would be hard to restore.”

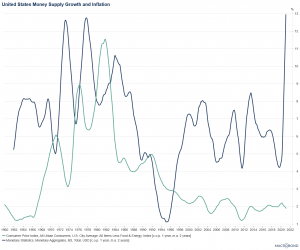

For you history buffs, the goals of the Federal Reserve changed quite substantially in 1977. Prior to the Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977, the Federal Reserve was focused on price stability and liquidity in the banking system to fend off the sort of banking panics we experienced in the early twentieth century. The 1977 legislation, however, added new goals—goals that have muddied the objectives of the Federal Reserve’s actions ever since—that required them to also focus on trying to achieve full employment. With this sometimes-contradictory new goal, the Federal Reserve’s attention to price stability lessened. Given the muted inflation environment through the 1990s and 2000s, the Federal Reserved gained confidence that it could tackle almost all problems with added monetary stimulus. It sounds like a fine idea, until you look at the chart below, which shows that dramatically increasing dollars in the past has led to inflation. In the late 1970s, it led to stagflation (i.e., low economic growth and high inflation). Note that today’s stimulus packages create a jump that surpasses even what was experienced in the stagflation days of the ’70s.

And what comes after a fast and large growth in dollars into the economy? Using the 1970s maybe too simplistic (and we definitely do not have abundant data) but we do know that in that era, the result was very high levels of inflation.

Mr. Volcker died in December 2019, and we fear that many of his ideas about our monetary system may have died with him. Two of his statements resonated with us: First, “The point was that the Fed should not be looked to as lender of last resort beyond the banking system.” And second, “My view, widely shared, is that it is inappropriate for an institution that benefits from the federal ‘safety net’ (for example, access to Federal Reserve liquidity, FDIC insurance, and less tangible comforts) to engage in risk-taking unrelated to the essential banking functions of deposit-taking, lending, and serving customers while sharing in operating a safe, efficient, and necessary payments system.”

And yet, in the spring of 2020, the Federal Reserve did exactly what Volcker argued against. The Federal Reserve established the Main Street Lending Program, Paycheck Protection Program, Municipal Liquidity Facility, Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility, and other programs with the intent of directly lending to businesses. In Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s own words, in front of the Senate Banking Committee in June 2020, “I don’t see us as wanting to run through the bond market like an elephant, doing things and snuffing out price signals,” he said. “We just want to be there if things turn bad in the economy.” (Of course, to some, driving yields lower and protecting risk-takers is the definition of snuffing out price signals.)

Powell and the Federal Reserve’s focus then was most definitely on aiding the economy through the forced shutdowns and working towards achieving full employment. And, recent comments have them adding climate change to their list of to-do’s. In the words of Fed Governor Lael Brainard, “Climate change and the transition to a sustainable economy also poses risks to the stability of the broader financial system. So a second core pillar of our framework seeks to address the macro financial risks of climate change.” The actions of the Federal Reserve under Powell could lead one to wonder if dollar stability is even in their top five worries.

Volcker’s efforts to squash the runaway inflation of the 1970’s—and the political and personal challenges he faced to do this hard and unpopular work—highlight for us that trust in the stability of the dollar was his and his board’s gravest concern. Now? Not so much.

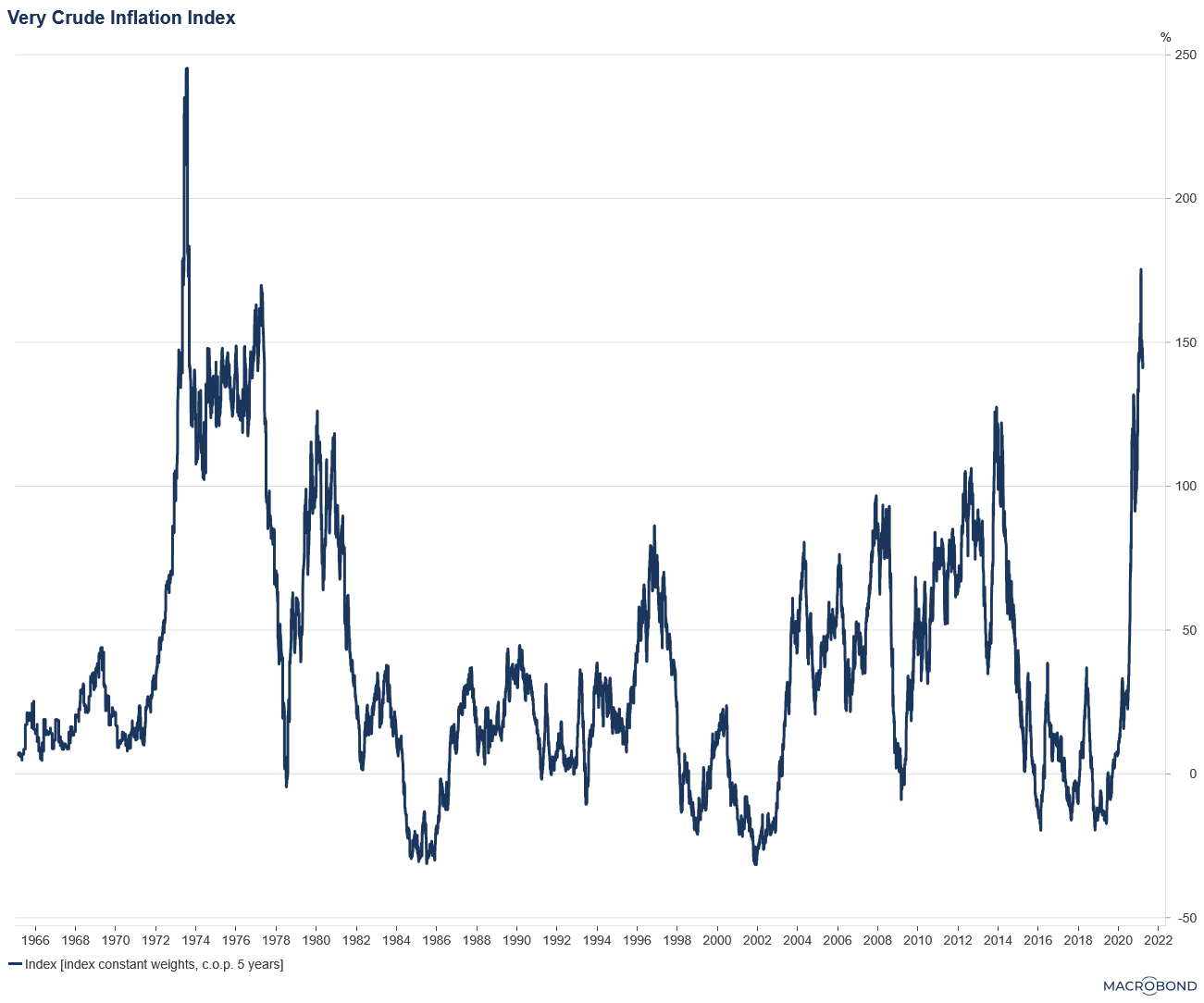

And this lack of focus on the essential stability of the dollar might just be why the young ones are looking for an alternative to rabbit pelts. They want an asset that aims for stability of the quantity in circulation (although, crucially, maybe not in value at this point). And it is not just the young ones. We look at a Very Crude Inflation Index (the VCII for us cool econ geeks) which tracks gold (for trading), soybeans (for food), and lumber (for shelter). The VCII weights food and shelter more heavily than trading. It’s a very crude index, as its name connotes, but sometimes looking at a less refined picture shows us more of the view.

And this lack of focus on the essential stability of the dollar might just be why the young ones are looking for an alternative to rabbit pelts. They want an asset that aims for stability of the quantity in circulation (although, crucially, maybe not in value at this point). And it is not just the young ones. We look at a Very Crude Inflation Index (the VCII for us cool econ geeks) which tracks gold (for trading), soybeans (for food), and lumber (for shelter). The VCII weights food and shelter more heavily than trading. It’s a very crude index, as its name connotes, but sometimes looking at a less refined picture shows us more of the view.

The VCII has hit a level of growth not seen since the early days of the 1970s, when the U.S. went off the gold standard. It’s still early days, and some could argue this is just a post-COVID spike, but we are seeing an odd combination of different generations agreeing to some extent. Both the young and some of the old are agreeing to some extent on the value of assets not dependent on government printing presses, with the elders remembering the 1970s and seeking to protect themselves with a finite asset like gold and the young ones appreciating the unique attributes available to crypto assets.

We end this newsletter with two quotations: one from a relative elder that has seen bubbles in the past and invested wisely around them, and another from a young one, on his initial reasoning for buying his first bitcoin in 2018.

Elder

“I don’t hate $BTC. However, in my view, the long-term future is tenuous for decentralized crypto in a world of legally violent, heartless centralized governments with #lifeblood interests in monopolies on currencies.” – Michael Burry via tweet, Scion Asset Management

Young One

“My thought was you shouldn’t trust government; most money is intrinsically tied to a government; and I think they will do something dumb like, oh, I don’t know, increase the amount of money in circulation by 100% and then raise taxes and cut its own legs out.” – David

One sounding skeptical on digital currency. Another sounding skeptical of fiat currencies. Both saying the same thing.

*We will be digitizing this newsletter and selling it as a non-fungible token (NFT) to the highest bidder. 😊

- We want it to be abundantly clear. Cryptocurrencies and crypto assets are highly risky things (we are not even sure if we really want to call them assets at this point). They are volatile, subjective in value, and often fleeting in their adoption. Be warned. ↑

- For those not hip to the crypto world (like us), the paper that first described Bitcoin entitled “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System” was authored by the mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto. For our analogy, we chose the young one to be named Satoshi Usagi where Usagi is Japanese for rabbit. ↑