“Everyone wants to live at the expense of the state. They forget that the state wants to live at the expense of everyone.” —Frédéric Bastiat

Not a day goes by without an article discussing inflation. And since that is the topic of this article, today will not be the exception.

Good inflation, bad inflation, deflation, stagflation, disinflation, hyperinflation… Did we miss any?

Most examples of very bad inflation, or hyperinflation, have occurred in smaller countries, where outside-their-control factors, such as energy costs and food dependency, caused havoc, and where the country’s politicians controlled the printing presses. (Keep that thought in your back pocket.) Maybe the U.S. with its reserve currency status and relative self-sufficiency, is structurally designed to escape long periods of high inflation? Might the same be true of Europe and Japan, the other major nations with reserve currency status?

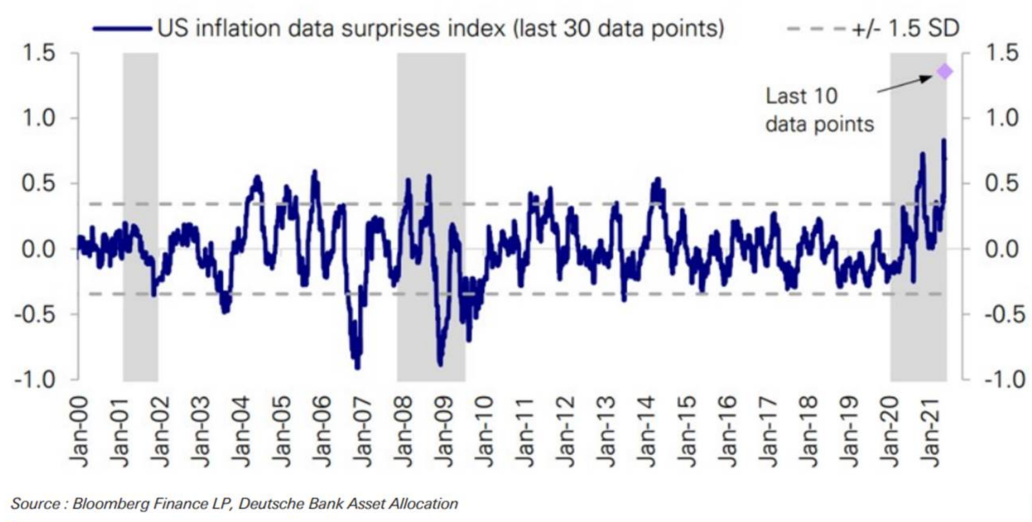

Regarding intermediate and long-term inflation trends, it’s not easy to build a logic chain that gets you to a confident outcome one way or the other. Analyzing the short term is easier. Pent-up demand from being sequestered for almost a year, supply chain disruptions that can take months or even quarters to fix, and the availability of easy money is driving up prices in goods, services, and real assets. We see it daily, with current inflation indicators at century highs.

Regarding intermediate and long-term inflation trends, it’s not easy to build a logic chain that gets you to a confident outcome one way or the other. Analyzing the short term is easier. Pent-up demand from being sequestered for almost a year, supply chain disruptions that can take months or even quarters to fix, and the availability of easy money is driving up prices in goods, services, and real assets. We see it daily, with current inflation indicators at century highs.

Given the data, it is not a question of if we have inflation (we do in goods and in asset prices), it is a question of if it can and will persist.

There is an argument to be made that persistent inflation is unlikely without a scarcity of core, non-discretionary inputs. (Think back to oil in the 1970’s). For inflation to take hold, households need to experience a steady increase in personal income or else, any rise in prices will need to be met with a reduction in spend in other areas. One only can spend what they can make, what they have saved, and what they can borrow. Keep in mind that inflation is inherently deflationary because it destroys future purchasing power.

When consumers must pay new and higher prices for certain goods, they then consequently will reduce what they spend on other goods—or eat into their savings to pay for them—unless the largest input to the U.S. economy, individuals and their efforts, can collectively push for sustained wage increases (not just one-time bumps). Recent data show considerable demand for labor, with wages moving up, but we would need to see this demand last beyond the post-pandemic re-opening process for it to figure significantly in the inflation measures. Even with a sustained increase in wages, there is a large hole in personal income to fill once the stimulus ends. If it ends. More on this in a bit.

When we think of today’s financial environment, we are reminded of the French economist, Frédéric Bastiat, and his parable of the broken window. The parable describes a child breaking a window, requiring the shopkeeper to spend money for a glazier to fix it. Those witnessing the event see the glazier is employed and therefore he and the economy benefit. Indeed, what would become of glaziers if panes of glass were never broken? But Bastiat argues that beyond the obvious one-time economic benefit the transaction in this example has for the glazier, if you were to extend the idea that destroying panes of glass repeatedly creates an overall good for the economy, he would have to cry foul. For what cannot be seen by witnesses is what could have been. The money the shopkeeper spent to fix the pane of glass can no longer be used in some other fashion, likely in an exchange that would have had a better and more enduring economic result. In other words, fixing the broken window prevented the shopkeeper from “replacing old shoes or adding another book to his library.”

We find this analogy pertinent to our current situation. The pandemic and the harsh economic toll of the shutdowns was like a stone going through a window—actually, like a lot of stones going through a lot of windows, all at the same time (…pause for effect…) and all around the globe. The economy was working well (though it had its issues that we addressed late in 2019) before the pandemic but has since required substantial funds to bring it back to something like the robustness that existed before. The fiscal and monetary response was arguably necessary because the suffering would have been much worse without the stimulus, but at what cost has this relief been to the future?

We find this analogy pertinent to our current situation. The pandemic and the harsh economic toll of the shutdowns was like a stone going through a window—actually, like a lot of stones going through a lot of windows, all at the same time (…pause for effect…) and all around the globe. The economy was working well (though it had its issues that we addressed late in 2019) before the pandemic but has since required substantial funds to bring it back to something like the robustness that existed before. The fiscal and monetary response was arguably necessary because the suffering would have been much worse without the stimulus, but at what cost has this relief been to the future?

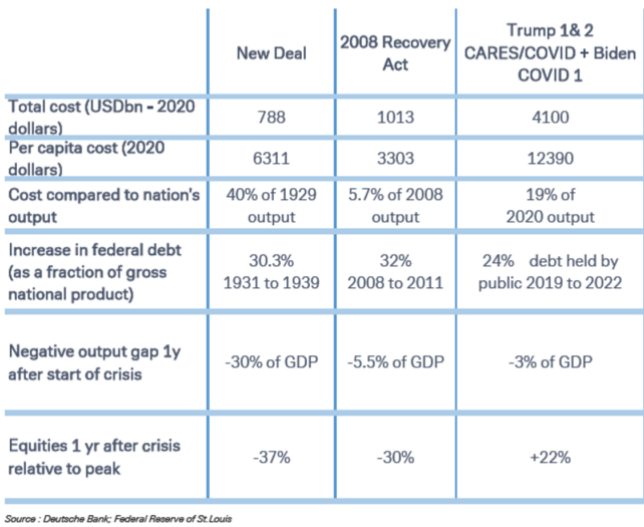

Let’s put the fiscal stimulus into context: The three stimulus packages to date total a little more than four trillion dollars (we find some humor in using the words ‘little’ and ‘trillion’ in the same sentence, but it seems fitting when we are writing about inflation concerns), which is four times the size of the federal government’s response to the 2008 crisis and more than five times after adjusting for inflation that of the New Deal. The table above shows the magnitude of government support relative to other metrics. Though not similar in all aspects, the federal debt added is comparable in size as it relates to the size of the economy.

Now, let’s jump back to the broken window parable. With lots of windows broken and the government coming in to fix those windows, the demand for glass goes up, and the demand for glaziers goes up, and the demand for puddy goes up. Some folks even decide to use those government funds and put in all new windows, so the demand for casings goes up. And, since we are changing out the windows, should we all consider painting our houses now, as well? A growing concern is that the large influx of funds are all competing for a narrow set of goods/service/assets, pushing up prices temporarily. Is the money spent at those higher prices going to be rewarded with a higher future return? Or will prices adjust back down once the stimulus passes resulting in a near-term loss that hurts future consumption?

The broken windows analogy seems particularly fitting given the current spending environment. Home Depot and Lowes are seeing significant growth. Furniture stores are quoting lead times of 6 to 9 months for deliveries. And try to find a contractor these days… No question those stimulus payments have aided consumers’ actions to better their homes. But is that sustainable?

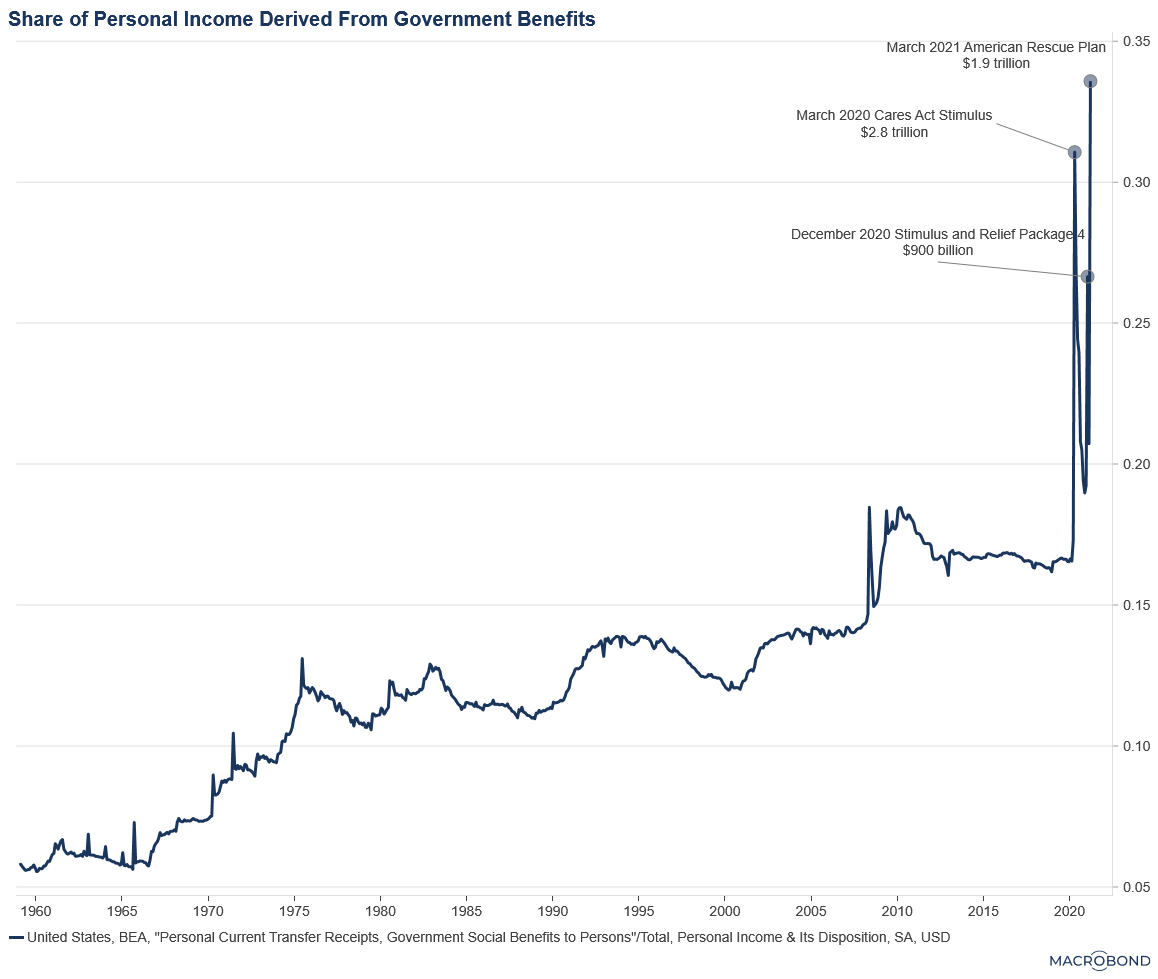

We have mentioned the size of the stimulus in the context of history but let’s also look at it as a percent of personal income because someday, one supposes, the productive sources of income will need to offset the temporary government benefits.

We have mentioned the size of the stimulus in the context of history but let’s also look at it as a percent of personal income because someday, one supposes, the productive sources of income will need to offset the temporary government benefits.

As the graph above shows, government outlays total about 33% of personal income. Government benefits (think Social Security, Medicare and welfare programs) had been trending up as our population ages, and it was in mid-teens as a percentage of income prior to the pandemic. The stimulus payments have now more than doubled that government spending. It was a needed boost when personal wages abruptly dropped 10% at the start of the pandemic. But is that level of support sustainable?

The strong government response has manifested itself in increased demand within targeted areas of the economy. What investors’ fear (and what the Feds hope, to some extent) is that the scarcity of certain materials and skills will drive an enduring upward move in inflation across a growing portion of the economy. The jury is out if that will happen. And while politicians might want ongoing stimulus—thinking money is free—it will be the bond market and the Federal Reserve that will influence interest rates, if they see price increases becoming permanent. Even a small adjustment up in rates can bring about material ramifications in what is a highly indebted economy. As we were told growing up, in good times, one looks at how much debt they can afford. In bad times, one reflects on how much debt they have.

The number and intensity of inflationary warning signs is ticking up, and we wonder if the economy will allow that to continue. Or will these factors lead, as they have for the past 30 years, to deflationary tendencies?

Attempting to weigh the likelihood of either outcome requires more time. One element that might drive the outcome is the interaction between asset pricing and consumer spending. Why? The Federal Reserve has studied the connection between people feeling wealthy and their spending habits. That research estimated that the dotcom boom in the late 1990’s added 1% to 2% of GDP growth per year. Today, some analysts think the wealth effect is getting stronger because people can more easily access their retirement account balances. Compare this to the relatively recent past, when corporate pension systems, outside the view of the consumer, held most of a person’s investable wealth. Now, more than ever, people have a daily view of their wealth through their retirement savings accounts and online estimates of home value. This feeds into their spending habits, arguably, more quickly.

Keep the following in mind when thinking of consumer spending:

- More than 70% of U.S. economic activity is driven by consumer spending,

- 50% of consumer spending is discretionary, and

- The wealth effect on consumer spending has increased as more consumers rely on self-directed investing versus the old days of defined benefit retirement plans.

Combining the wealth effect with the knowledge that 70% of the economy is services-driven (i.e., quick to be turned on and off) and that 50% of the consumer spend is discretionary (i.e., painful to lessen but do-able), one can argue that consumers flex their spending habits quickly, potentially mitigating the idea of sustained inflation.

When we started drafting this article, it was with the belief that inflation is perking up and with a growing concern that the Federal Reserve was losing control of it. We still see inflation as a concern, but through the writing and research process, we have convinced ourselves that deflationary episodes are also still a concern.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, we see the growing fears of hyperinflation as unlikely. Hyperinflation comes from a lack of trust in the currency, and we do not see, at this time, the Federal Reserve willing to take actions that compromise that trust. They are taking actions that make us concerned (as we have written about previously), but there is a long road from here to extreme inflation. If the printing presses are controlled by the Fed and not the politicians, we see little reason to think the worst.

So where does that leave us?

We are optimists who believe that only the politicians running our government find high inflation beneficial. (Sorry, but we are going there!) They get to write checks to their electorate as a means of maintaining their power, raising taxes (which is deflationary) to eventually cover their obligations. (Refer to the quote at the beginning of this article.)

The Federal Reserve governors are less inclined to allow high inflation than the legislative branch because it could cost them their jobs, and they know it destabilizes the balance sheets of the banks. Also, they have the tools readily available to guard against runaway inflation. However, the dual mandate of price stability and full employment puts the Federal Reserve on an ever thinner high wire, with high rates themselves promoting instability since a highly levered financial system will seek to de-lever and spend less.

And then there is the global investor base…

Uncontrolled inflation is bad for the bond and the equity markets. Deflation is bad for equity markets. And excessive government spending might lead to malinvestment, and a detox process, once it dries up. We also sit at historically high valuation levels in the equity market. All of this explains why at Auour, we still sit in a defensive position.