“In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.”

Benjamin Graham (father of value investing)

This is not a time for relatives. Don’t worry, Mom, we aren’t referring to family. We mean that justifying an investment based on its attractiveness relative to the prices of other assets is unwise. Over the last thirty years of our investing and experience during two asset bubbles (which we wish would not happen so often), a common perspective shift is apparent: market participants move from talking in absolute terms during market bottoms to speaking in relative terms at market tops. When investment markets are at depressed values, investors focus on the earnings capacity of a firm and how its current price could produce a robust return. Or investors focus on how you can purchase an asset for less than its replacement value, meaning you effectively get a productive asset on sale. During the market topping process, however, investors switch to thinking about how a certain asset class is valued more cheaply than another, without regard to the absolute price. Or investors focus on justifying a company’s valuation based on recent accelerated growth and extrapolating it to never-ending heights.

Today, we need only look as far as the words of Jerome Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, for an example of this “relativity.” He said recently that equity markets are not overly expensive when compared to the high prices (i.e., low rates) of bonds. “Admittedly P/Es [current price divided by expected earnings] are high but that’s maybe not as relevant in a world where we think the 10-year Treasury [rate] is going to be lower than it’s been historically from a return perspective,” he stated during a December speech. He neglected to mention he set the interest rates artificially low and has aggressively bid up the prices of bonds in response to the pandemic and the recession it wrought. These forced actions are what pushed rates toward zero.

We have stated many times that market tops and bottoms should be viewed as processes rather than discrete points in time. This is especially true with the tops. We highlighted in our last newsletter, “Bubbles,” our experiences during past periods of blind faith. Significant cracks were showing in late 1999 and early 2000, yet the market held up for most of 2000—and then proceeded to decline for three years. Many analysts and publications from late 2000 asked, “Has the market bottomed?” It hadn’t. The NASDAQ proceeded to lose 80% of its value, and the S&P500 50% of its value, over the next three years.

We can also refer to the most recent bubble (the Great Financial Crisis) for evidence of this phenomenon of market tops being processes: mortgage defaults were rising throughout 2006. In May 2007, Bear Stearns attempted to save two of their large mortgage hedge funds, infusing them with more than $3 billion in new cash. The hedge funds failed within a month. The equity market did not respect even that signal and maintained its elevated position until late 2008, when the Lehman bankruptcy shocked investors into respecting financial risks. The bursting of the housing bubble resulted in a loss of more than $8 trillion of perceived housing value (as estimated by Jeremy Grantham of GMO). It is hard to comprehend how so many market experts and participants could have miscalculated the value of technology stocks in 2000, or of housing assets in 2007, to such an extent.

The explanation for these seemingly gross miscalculations likely lies in the way investors incrementally vote the market higher as relativism takes hold and short-term success bolsters confidence in long-term optimism. Yet, at some point, the greed eventually weighs heavy, resulting in collapsing prices—and then extreme fear—as we experienced in the bursting of past bubbles.

The problem with relativism when justifying investment decisions is its foundation falls away as other assets start declining. It is a key component in our philosophy that in times of duress, all assets are at risk, with few investments offering principal protection. In the case of Mr. Powell’s quote above, what if interest rates moved up, against the will of the Federal Reserve? (This is not the current consensus view, but it has happened repeatedly in our history.) Without any change in a company’s market positioning, earnings power, or defensibility, its equity value can be dramatically revalued. In other words, with unchanged business fundamentals, that equity will now look more expensive relative to safer fixed income instruments.

Investors become “trained” by short-term market movements. They change their analytical framework from one of assessing investment fundamentals to one of debating and trading on only macro factors (e.g., the expectation of monetary and fiscal stimuli, etc.) and the incremental change of those factors. They gradually shed their concern about the durability of a company’s business model and its future earnings stream’s ability to support its valuation.

And this is why we see the current environment as a fight between relatives and absolutes, with relativism currently on top. However, we tend to believe Mr. Graham that the weighing machine will kick in, and absolutes will win in the end. As momentum subsides, which it always has in the past, the weight of reality will take hold, and the foundational aspects of investing will once again become important.

One current example of market relativism: many think with the introduction of vaccines, a pro-cyclical approach should be taken as the world economy comes out of a very sharp, yet brief, recession. (Refer to our Fall 2020 newsletter, “Two Narratives.”) The typical game plan at the end of a recession is to close your eyes and invest in stocks, industries, and sectors that benefit from an economic recovery. We see a few issues with this line of thinking at this time.

During a recession, the economy sees a retraction in risk behavior that traditionally results in

- bad business models shutting down (yet the likes of Nikola rallied without any revenue or a durable business model),

- mergers occurring within weak industries to reduce capacity (yet airlines maintain their independence),

- companies’ inability to go public (yet the U.S. experienced more initial public offerings in 2020 than that experienced in 2000 internet bubble),

- deeply indebted companies working down excessive debt (yet 2020 was a record-setting year for all forms of debt issuance, with corporate debt levels rising to all-time highs),

- increasing pessimism around the likelihood of an earnings recovery (yet expectations are for a full recovery faster than experienced in any cycle over the past 50 years), and

- individual investors shying away from risky investments (yet we have experienced unprecedented activity in risky derivative markets).

Recessions act to clear out the weak and reinforce the good behavior of the strong. They have traditionally led to more sound investment opportunities. The evidence today suggests we are not experiencing the typical cleansing we are accustomed to. Is it different this time? Or, are we continuing to act in a relative manner, increasing the risks of a far greater and more painful event that drives us back to the absolutes?

Let’s look at some absolutes.

Let’s look at some absolutes.

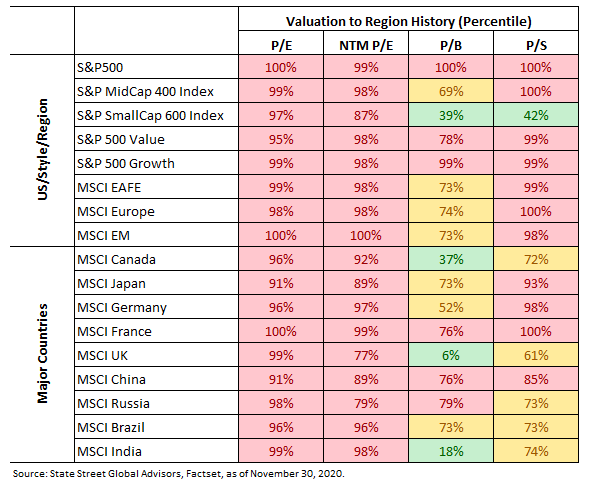

Valuations across almost all equity classes are at, or are very near, the highest levels experienced in recorded history (including the dot-com bubble). In our memory and reading of market history, robust and enduring investment cycles have not started from our current position.

There is no precise method of valuing a firm, so we use different perspectives to determine value. No matter the type, size, or region, almost all asset categories today are trading at their historical highs. Some might argue that depressed earnings prevent earnings-based valuation approaches from being a good predictor. However, the valuation process looks forward, at earnings expectations that assume a profit recovery happening in less than two years’ time. (This means that corporate earnings would surpass their pre-recession highs). A review of past recessions suggests that two years would be half the duration of prior profit recoveries. And two years is but a fraction of the time that the deepest economic contractions have taken to recover. It might be different this time… but it might not.

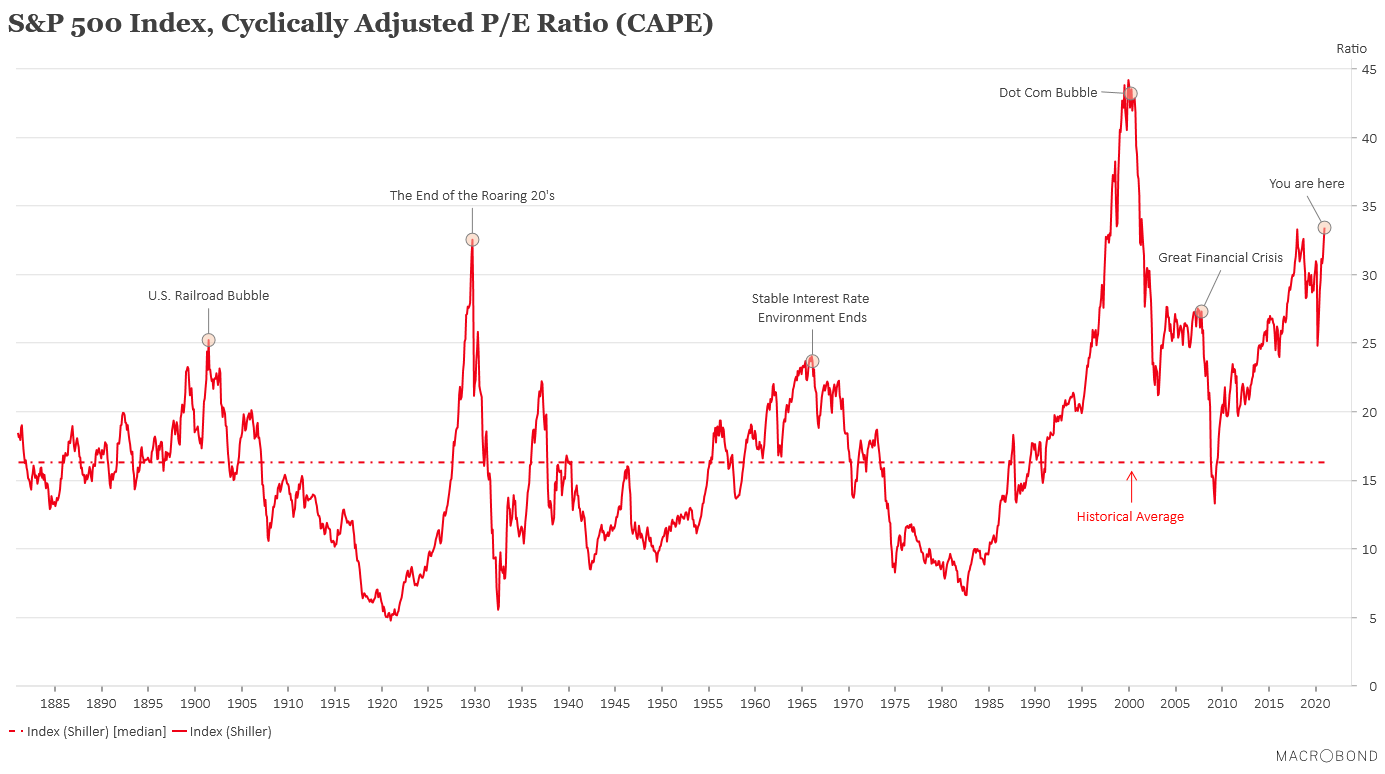

Let’s stay on the valuation train and look at how longer-term indicators are sometimes used to attempt to see past the earnings volatility driven by economic cycles. Like all valuation indicators, the Shiller Cyclically Adjusted PE (CAPE) measure has not been a good timing mechanism for determining when to buy or sell. However, it has been a strong indicator of the presence of bubbles. Please remember, at Auour, we do not look to valuation as a strong factor in timing future market movements. Instead, we see it as a risk factor, helping us ascertain the severity of any future correction. The farther from the historical average, the higher the concern that a future correction will be painful.

As the technology bubble of 2000 demonstrated, bursting doesn’t always happen quickly. The word bursting really calls up an inaccurate image altogether. The puncture might be dramatic, but it can take years for valuations to settle on a solid foundation. It is difficult to precisely time the bursting of a bubble. It is even more difficult, in our opinion, to determine the trajectory and length of the ensuing  slackening. What we do know is that the more highly an equity is valued, the lower its future return potential. The risk of loss becomes high.

slackening. What we do know is that the more highly an equity is valued, the lower its future return potential. The risk of loss becomes high.

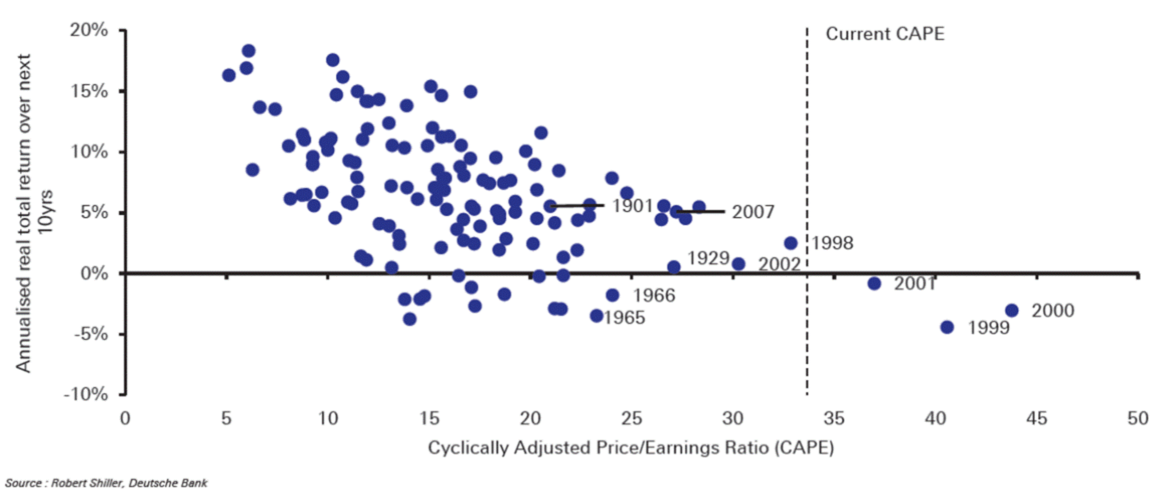

The chart below shows the equity market’s current valuation in a historical context. It reveals historical 10-year forward returns for different levels of the CAPE ratio. If history is to repeat itself, the current environment may offer a very unrewarding future.

The chart below shows the equity market’s current valuation in a historical context. It reveals historical 10-year forward returns for different levels of the CAPE ratio. If history is to repeat itself, the current environment may offer a very unrewarding future.

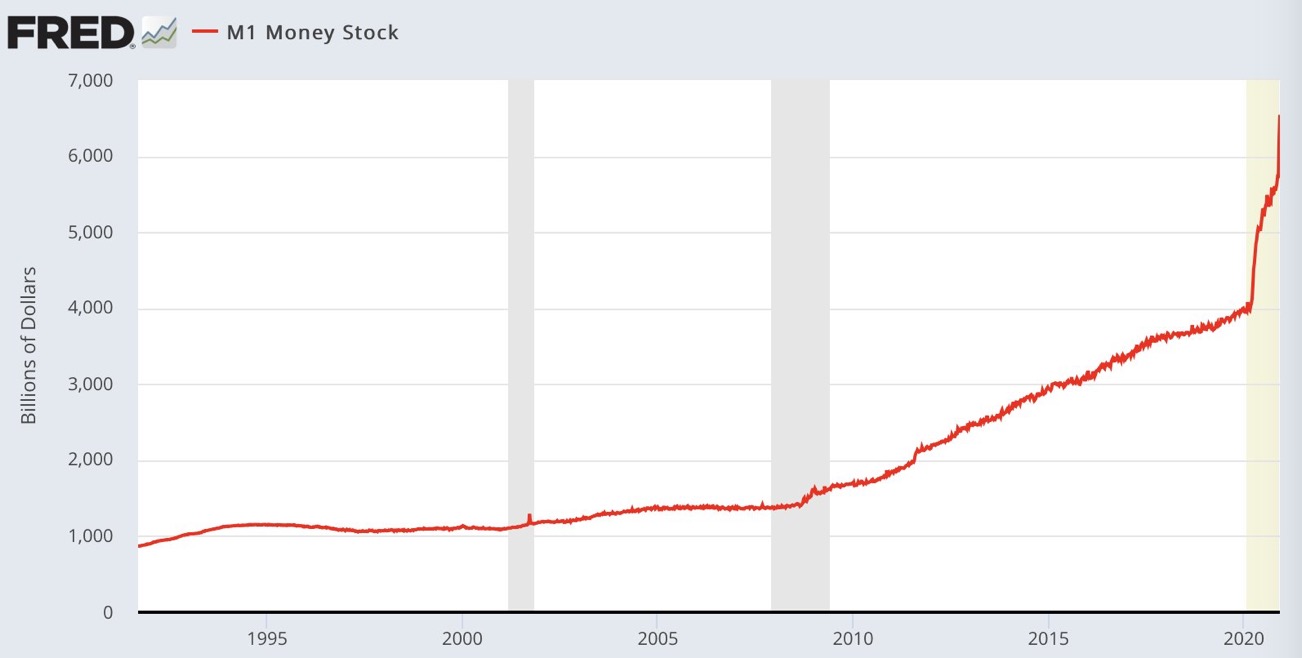

As depicted in the S&P 500 CAPE Ratio graphic, valuations, as they present themselves today, are the highest since the 2000 internet bubble and, at least to us, the cause is clear: they have been created via the significant monetary liquidity the central banks facilitated. As expressed in the M1 Money Stock graphic, money supply growth is extreme by any measure.

We have discussed in the past how central banks possess a hammer and so see many problems as a nail —adding monetary stimuli no matter what issue the world is facing. Greed is the common element to all past bubbles and this one is no different. However, the central banks’ actions to suppress economic troubles are feeding speculators’ confidence that the greater risk is being out of the market rather than in it. The actions are a clear example of moral hazard.

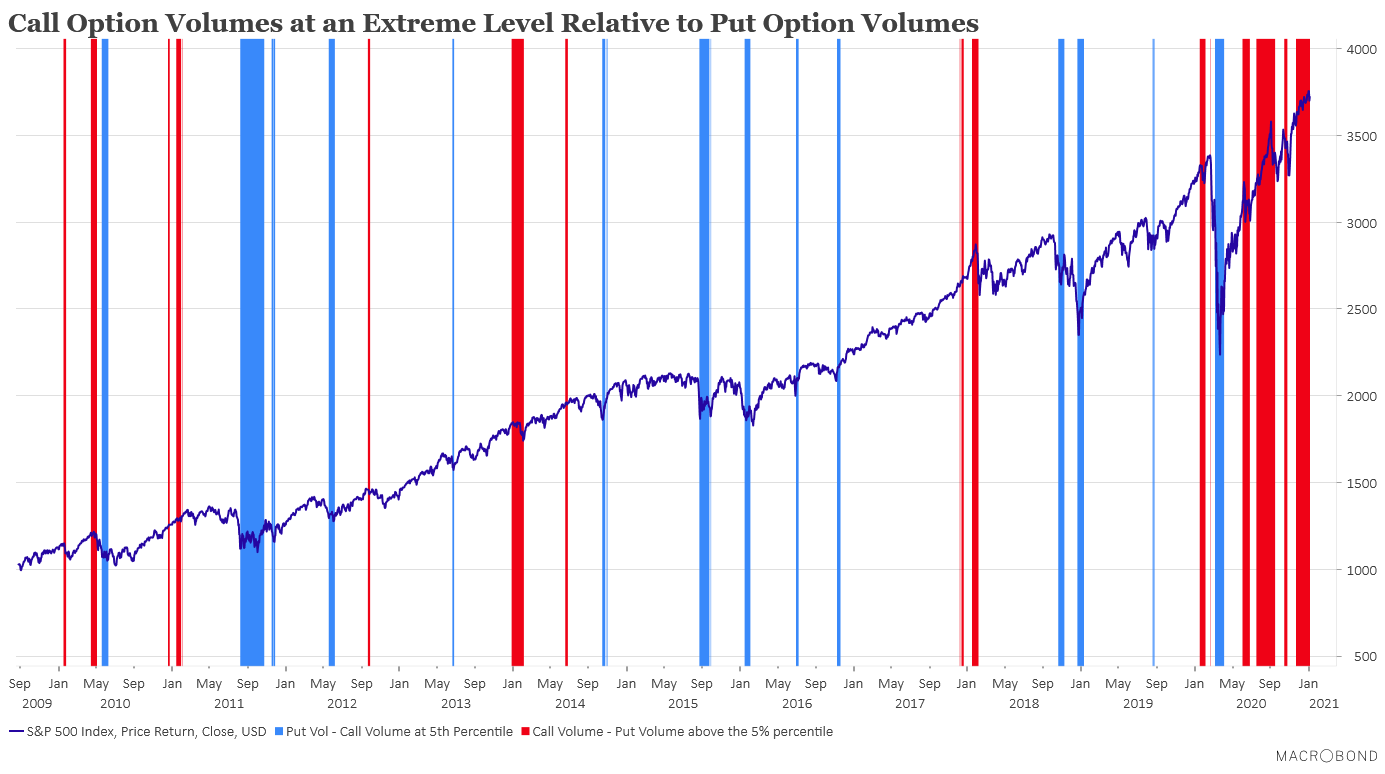

As a sign of risk behavior of individual investors, new brokerage account growth hit records in 2020, and the use of options as a form of market-betting has been extreme. At Auour, we track the imbalance between call options (a form of buying stocks) and put options (a form of selling stocks). The graphic below shows the extremes in the imbalance, where we can think of red as indicating heightened greed and blue, fear.

As a sign of risk behavior of individual investors, new brokerage account growth hit records in 2020, and the use of options as a form of market-betting has been extreme. At Auour, we track the imbalance between call options (a form of buying stocks) and put options (a form of selling stocks). The graphic below shows the extremes in the imbalance, where we can think of red as indicating heightened greed and blue, fear.

We sit at a point of significant speculation in the options market and excessive growth in the money supply. The former is fleeting, and the latter has always resulted in inflation.

At some point, interest rates will rise no matter the intention of the Fed, and bond investors won’t care that the current equity market’s high levels are being justified on the expectation that rates won’t rise. In investing, we were taught to look for multiple “pros” to justify the purchase of an asset, knowing that having only one makes an unsteady justification. Right now, it appears that all investments are riding on only one pro: low rates.

Conclusion

William Sharpe, one of the fathers of modern investing, describes risk as unexpectedly losing a substantial amount of money over a short time. We see such risk being historically high.

Was the market correction (a 34% loss in 23 trading days) in the first quarter of 2020 the bear market, or was it the start of the bear market? Whichever you argue, it is hard not to see it as a tremor, a harbinger of what may be a new phase to this investment cycle. It is why we continue to stress a cautious tone. Our conservative positioning has allowed us to continue to participate in the market’s advances, yet it reduces the risk of extreme damage to our clients’ portfolios.

The quote at the beginning of this commentary was a comment about the struggle between short-term and long-term investing. Over short periods, the incremental investor votes with dollars (of which the central banks have provided many), pushing assets higher as success breeds confidence in continued success. Momentum takes hold as majority thinking drives ever higher pricing. However, at some point, the weight of the high valuation will need to be justified by the earnings of the asset.

Sometimes the results of a popularity vote can express current whims but have lasting ramifications. Just look at the early 2016 British Internet referendum where the public was asked to vote on a name for the lead boat of a new fleet of underwater vehicles. The overwhelming winner was Boaty McBoatface.