“The economic problem is that the material fruits of the United States’ engagement with China (and the post-1980 globalization more generally) have been very unevenly distributed…”

—Arthur Kroeber, Gavekal

The Quarter in Review

It was not a bad quarter! U.S. equity markets were very strong across all styles and sizes. We moved past the impact of February’s dive in this quarter, and although you can point to different reasons to justify calling it strong, clearly the economy was the primary factor, with the U.S. continuing to buck the trend of slowing growth in international markets.

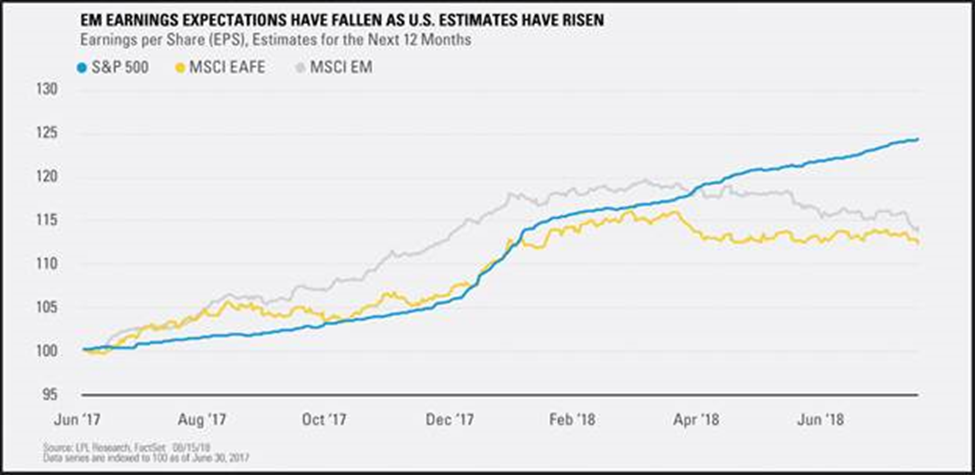

On that note, the international economy has been missing the growth expectations set at the beginning of the year, especially in emerging markets. It was a strong asset class in 2017, when we were celebrating synchronized global growth, but emerging markets are now posting a negative return for the quarter and for the last twelve months. Even the developed international markets are experiencing increased stress, and local growth estimates are being revised downward.

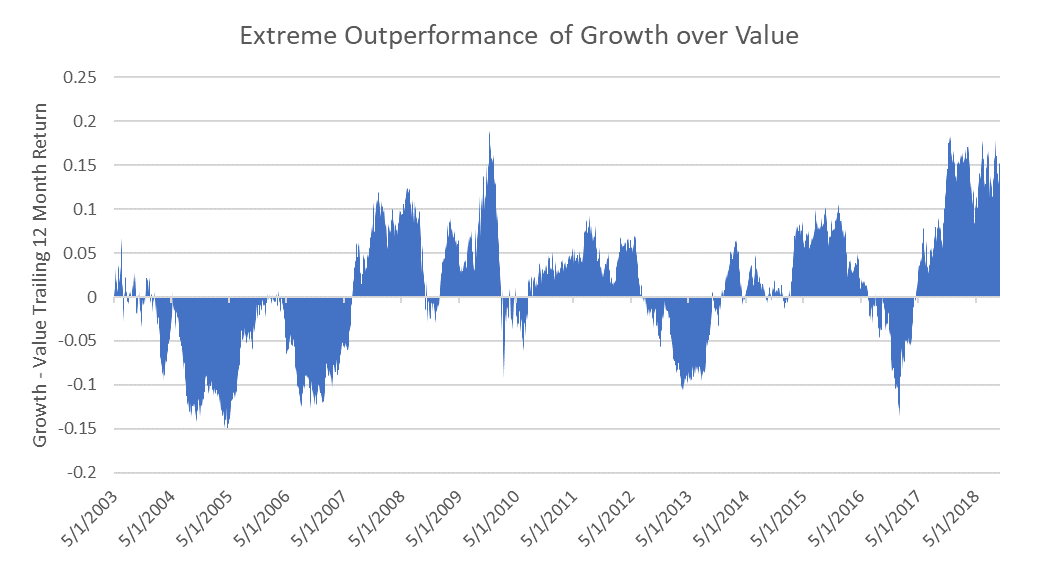

Growth companies continue to outperform the market overall, and as we have stated a few times in the past, this is consistent with the later phase of an investment cycle. The gap between growth and value has reached extreme levels.

The fixed income markets continue to be soft as the improving employment backdrop is buffering wages and providing support for continued rate rises. After a 35-year one-way bond market, the change in direction will not be painless.

Buffeting the Disconnect

Our 2018 outlook opened with a discussion of the different types of market bubbles. Today, we’ll recognize two types of enduring downturns. One is a cyclical reset of corporate earnings, driven by prior excess spending (either by consumers or corporations). The other type of downturn is driven by a banking crisis, wherein a rapid inability to finance debt causes banks to distrust each other and their customers. These banking-crisis downturns produce an even greater level of spending reduction than the cyclical reset of earnings. We sit in a precarious time: both kinds of downturns may be on the horizon, but in different geographies.

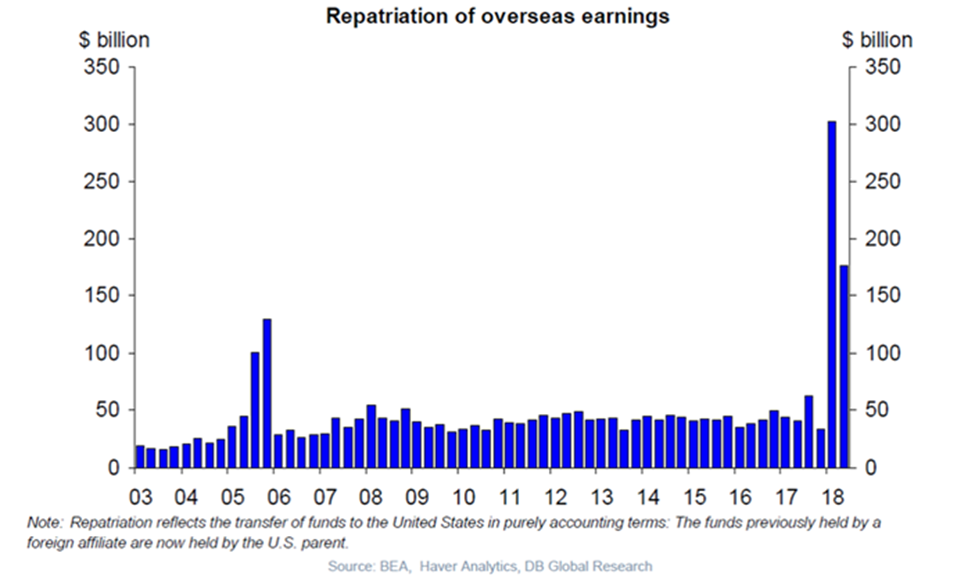

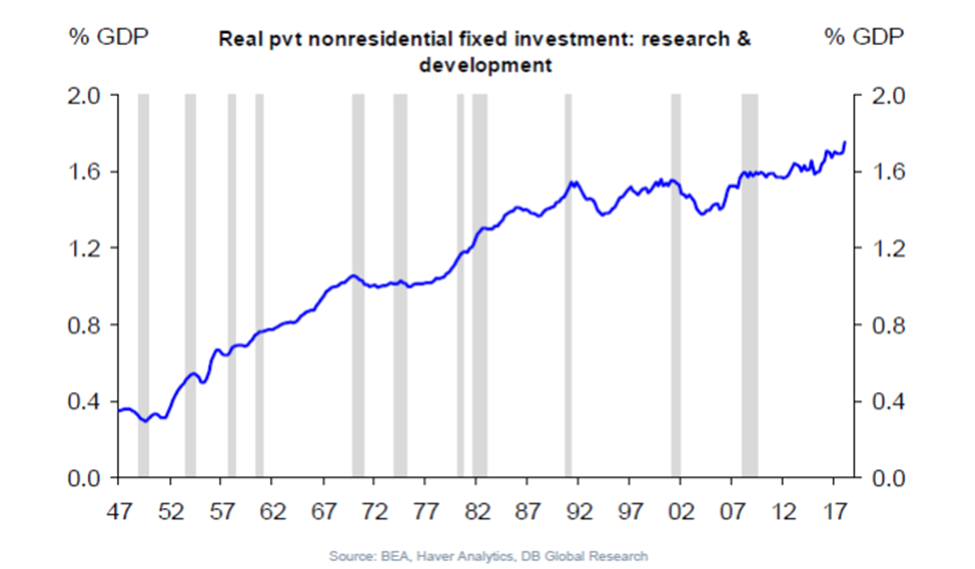

By many measures, the U.S. is sitting pretty. Employment and wages are growing, taxes have been cut, regulations are less onerous, corporate cash is being repatriated, and capital spending is picking up from ultra-low levels. The U.S. is even hitting new highs for investments in research and development, a key indicator of future growth and productivity improvement.

What could go wrong? Well, some might argue that the U.S. is experiencing a sugar high due to lower taxes and their stimulative effect on end demand. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, and the negative repercussions from such an effect would not be as lasting as those experienced in 2008. However, there are growing instabilities that could change sentiment and, therefore, consumer appetite to spend.

As Warren Buffett has repeatedly said, “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.” At this time in the U.S., the easing of trade frictions with our neighbors and the impressive growth in the economy has continued the bullish actions of many investors and investment offerors, especially in the bond markets. The markets just witnessed one of the largest debt offerings in history, which Comcast used to purchase Sky Broadcasting. The demand for the deal could be characterized as spectacular, and the thirst for corporate debt is unquenched. This is evident even in riskier bond market segments. Leverage loans, for example, which had a total market size of $200 billion in 2005, have grown to almost $1.2 trillion this year. And, 80% of these loans today are considered covenant-lite, versus 25 percent in 2007.

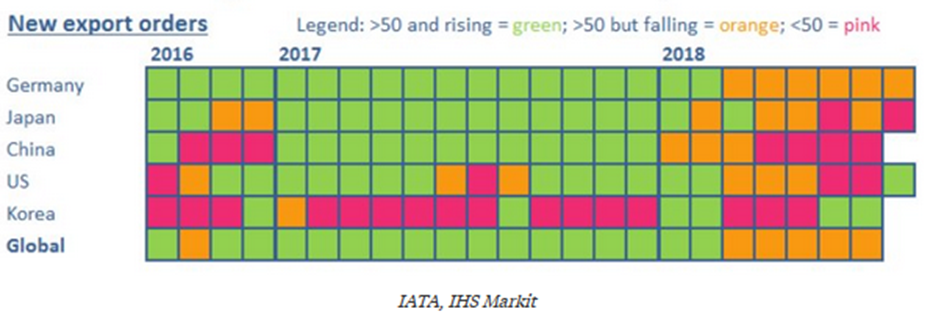

This market behavior is not surprising, given that the U.S. economy is robust. Inflation remains low, and with wages rising, consumer confidence is allowing corporations to build rather than retract. But how long can the U.S. maintain a robust growth trajectory when other parts of the world are showing cracks in the armor, as we can see in the case of exports?

It may be extreme to use the term trade war to describe the current U.S. approach to global trade negotiations. Rather, the world is adjusting to a new U.S. mission: moving from a focus on leveraging low-paid global laborers to one that now appears to be more protective of U.S. citizens and its manufacturing base. Though the negotiating tactics involve a lot of saber rattling, we think of the current situation as a trade reset.

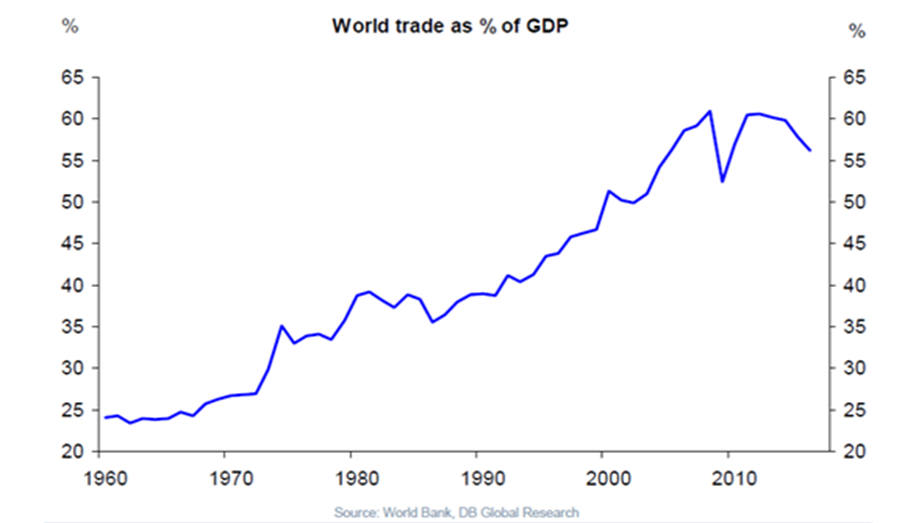

No matter the semantics, the result has been a growing fear of future disturbances. This fear, when you consider the magnitude of global trade, will not leave any region insulated. It is especially true of large U.S. firms, where more than one-third of sales comes from outside the U.S. The rebalancing of global supply chains will therefore be a headwind for those markets that benefited the most from international trade over the past 20 years.

Emerging markets, in particular, China, have already been impacted. Growth in China, the largest country within the emerging markets sector—considered by many to be the assembler to the world—has been softening. Recent business activity surveys indicate further weakness. Although official government statistics do not portray the same concerns, evidence is mounting that something is amiss.

Today, another Warren Buffett saying comes to mind, “You only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out.” China has been seeing a pickup in corporate borrowing concurrently with profitability dropping. Coincidentally, corporate default rates in China have been rising. Add to this that the $200 billion peer-to-peer lending sector in China has seen more than 400 networks shut down this year, with a preponderance being exposed as Ponzi schemes—note this has all occurred before the U.S. tariffs have even been instituted—and we are, unfortunately, seeing more skin than we would like to with the retreating economic tide.

It’s not just China experiencing a slowdown. The IMF lowered their growth estimates for all regions except the U.S., mimicking the market’s changing expectations. Though trade is blamed, the reasons are multifactorial. In Europe, we have the continued uncertainty regarding Britain’s exit from the E.U. There is also increasing

uncertainty regarding Italy’s ability to weather their banking crisis and their need for fiscal stimulus, which goes against E.U. rules, stoking fears that they, too, will exit the common currency.

Finally, we have concerns about the health of the economy in countries where we had hoped to see additional growth, such as India. Last week, the Indian government took over the IL&FS, the largest infrastructure owner in India, in an effort to contain what some have called Lehman-like risk, given the exposure of many of the largest banks to this lender. The cost to rectify the situation is expected to be large adding to the growing fear of emerging market stability.

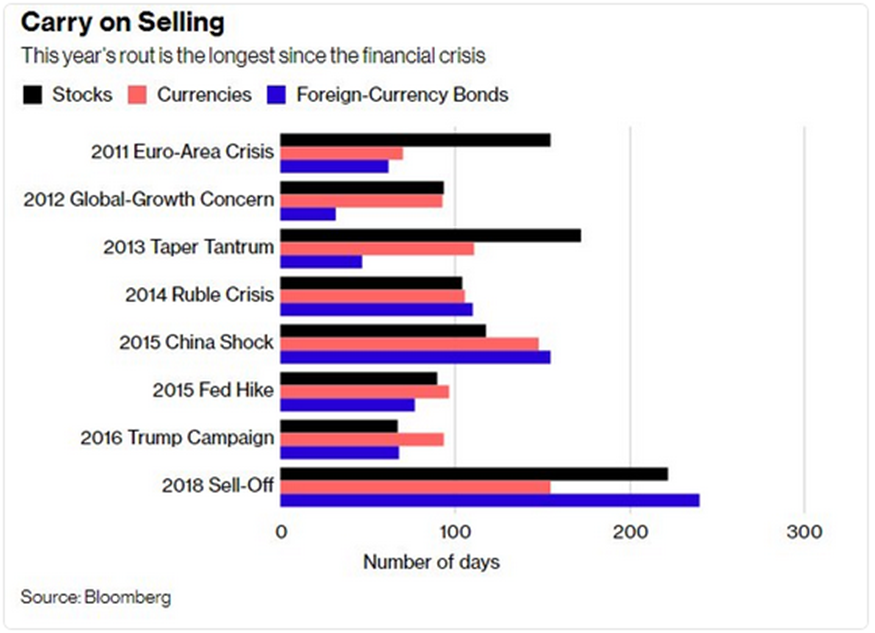

Of course, there are always areas of concern. And none of these concerns independently predict a global downturn. But when one signal follows another and another, the situation takes on a different feel. The notion that the signs are isolated events starts to ring false as more and more of these “isolated” events happen. Given all the variables involved, it is nearly impossible to forecast the world economy. It is much easier to detect a change in the risk appetite of global investors, which in turn can affect the economy. We think we are starting to see these signals of a lower appetite for risk now.

Conclusion

We spent 2017 fully invested and started the year that way, too, acknowledging the improving global growth environment. That changed in late January as our models raised cautionary flags. At the end of January and again in early April, we reduced the risks across all portfolios through a reduction in international equities (developed and emerging economies) and the raising of tactical cash, while still maintaining a positive outlook on the U.S. market. Those adjustments, in hindsight, were well timed. The U.S. has continued making new highs while growing fears internationally have created a large drag on international performance. Gaps in performance rarely remain permanent. The inter-connected nature of our global economies argue that the gap will close, with the U.S. eventually following.

We maintain our belief that the issues we see as potentially disruptive to the global economy are not necessarily U.S.-focused. However, the U.S., even with its superior growth, is unlikely to come through unscathed. While the U.S. has seen a reduction in centralized control of economic behavior over the past few years, some of our international partners have been moving in the opposite direction. These actions are not conducive to increasing global growth, and they present a vulnerability even to the U.S. that must be worked through.

With the growing concerns in certain regions, another Buffett quote comes to mind. “The most common cause of low prices is pessimism—sometimes pervasive, sometimes specific to a company or industry. We want to do business in such an environment, not because we like pessimism but because we like the prices it produces. It’s optimism that is the enemy of the rational buyer.” We believe we sit in a growing pessimistic environment globally, and like Mr. Buffett, will aim to invest your savings at better prices. And, again like Mr. Buffett, we look to those pessimistic times as opportunities as we are optimists on the long-term trend of humanity (though some days are harder than others).